Feel free to fire back on this one, but I don’t think there was a real “song of the summer” in 2025. No album of the summer, no unifying, Brat-like lime green sheen to cast over late summer nights out. What is a girl to do without an album to tie her entire identity to from the months of June to August? One must pull herself up by her headphone cords and pick an album herself.

Alas… au revoir Brat, and E komo mai (welcome) Kolohe Kai Summer! The Pacific Island Reggae group Kolohe Kai (closest Hawaiian to English translation: “rascal in the water”) splashed onto my radar last year during the height of Brat-topia and rose up my listenership ranks on a particularly blazing Austin day this past May. I had just registered for the 2025 Honolulu Marathon, and it felt only right to listen to more Hawaiian artists as I train (and hopefully get to catch a few while we’re on Oahu in December! Eek!). Admittedly, it’s not all about culturing myself – Kolohe Kai Summer is also deeply ironic, 2009 surf crush, make-the-sounds-match-the-UV-index type playlisting. Honest or ironic, at the end of the day, I now wonder how Hawaii, and islands beyond HI, have developed similar rhythms with similar instruments, despite miles of ocean between each. Like why is the steel drum sound so uniquely “beach?” How does the ukulele scream “Hawaii” just by existing?

The answer is in part indigenous tradition, including oral tradition and instrumentation constructed from island material (e.g., bamboo nose flutes, drums made of gourds), and unfortunately, in large part, colonization in the late 1700s. Before being annexed by the United States in 1898 (and technically *still* occupied rather than “owned” by the U.S.), British and other European colonizers brought over (er, imposed upon Hawaii?) Christian spirituality (hymns, etc.) and their own instrumentation (guitars, etc.). Despite this imposition, Hawaii has triumphed sonically, blending their own ancient and sacred traditions of mele (chanting, singing) and hula (dancing) with the instruments of colonizers, deriving the ukulele from Portuguese cavaquinho (“mini guitars”). Music has always been a strong form of resistance, activism, and cultural preservation – maybe it’s co-opting these at first conquistadorial sounds and instruments and making them their own that is a true reflection of indigenous Hawaiian resilience.

It might just be me, but Hawaiian music as we now know it has a distinctly vintage yet fresh look and feel, somehow a little bit ‘60s all the time? But it turns out, Hawaiian music (the blended traditional/colonized sound) made its way to mainland USA in the early 1900s and had the highest volume of recordings of any genre/style sold in 1916 (!). This opened a whole ‘nother can of worms for me, immediately googling “how was music even recorded in 1916” – think, artists play acoustic music into a large flare horn, which was saved (?) onto a wax cylinder, eventually a disc (hi, vinyl records). No slight to any of my history teachers, but I didn’t picture an almost WWI America vibing to coastal tunes. In my mind, it’s perpetually Meet Me in St. Louis until the 1930’s/Great Depression (deeply inaccurate, but my vision nonetheless). Now I’ve got an image of Judy Garland forlornly singing “Mele Kalikimaka” while looking out a stained glass window… digression aside.

My question persists though: how did so many disparate island cultures connect to similar sounds? Taking reggae, the dominant island genre, as an example. Reggae flourished at the confluence of African rhythms, European folk, and Caribbean indigenous influences, a beautiful example of how island music buoyed those oppressed by triangular trade. I’m torn here, though, on if this really is beautiful or actually quite awful that Afro-Jamaican music is forever permeated by unwarranted influences. Of course, the result (reggae) changed music globally forevermore, not only inspiring unity and producing anthems of joy, presence, and gratitude, but also bringing attention to colonization and resistance to it (hi, 2024 movie Bob Marley: One Love). I have a hunch that I’ll keep coming back to the same question in future writing: how does what we hear, as individuals and as distinct people groups, affect what we create, whether we like it or not, as simply as preference and hugely as cultural preservation?

Hawaiian Reggae, though, is a relatively new subgenre. Much like the Caribbean islands, the Hawaiian islands were objectively trespassed upon and remain occupied, with music as a microcosm of larger cultural shifts. Hawaii experienced a renaissance of Kanaka Maoli (“Native Hawaiian”) culture in the 1970’s, a revitalized practicing of hula and mele, and around the same time, thanks to radio and better music recording technology (so long, flared-horn/wax cylinder 1916 setup), reggae made its way to Hawaii. Ethnomusicologist Sunaina Keonaona Kale remarks in a conversation with the University of California regarding Hawaii’s relative adoption of reggae that,

“…reggae fits into Hawaiian cultural ideas about what music is. The nahenahe “sweet sounding” aesthetic is one reason. I think reggae is nahenahe. Kānaka Maoli and Afro-Jamaican people also share a connection through racism and struggles for decolonization. Hawai‘i is illegally occupied by the U.S. to this day. People tend to think that the political similarities are the main reason Kānaka Maoli have embraced reggae, and it is an extremely important one. But I tend to de-emphasize this point, because I see so many other things happening in conjunction with the political angle.”

I had at first thought, perhaps it’s less about our almost inextricable association of the island “sound” matching the island “vibe,” and much more about the shared experience of incubated indigenous tradition interrupted and forever altered by colonization that makes reggae so relatable and adoptable island-to-island. I see now that, reggae itself was another arguable intrusion upon the already robust and revitalized Kanaka Maoli culture.

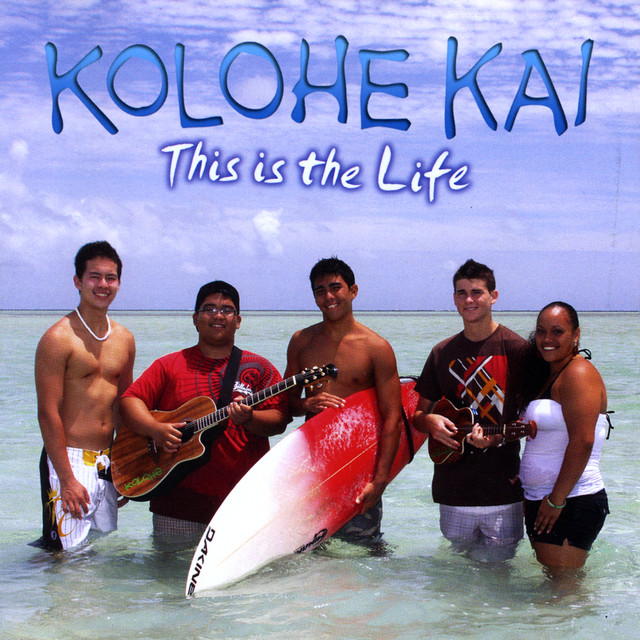

Funny, how this all began with the question of, “where’d we get the ukulele.” We’ve (I’ve) hop, skipped, and jumped to Kolohe Kai, arguably the most popular Pacific Island Reggae group ever, their lead singer Roman de Peralta an almost Disney Channel-esque Hawaiian heartthrob and their music deeply influenced by 2000s surf-y pop yet nevertheless echoing centuries of cultural resilience, intrusion, and adoption.

If I’ve lost you in the anthropology and ethnomusicology of it all, oops! God forbid a girl wants to know the political and sonic implications of her summer music obsession. Back to the main point from literally eons ago, what is a girl to do without an album to identify with? Enter: Kolohe Kai Summer.

In order to subscribe to Kolohe Kai Summer, it’s as simple as over-streaming their debut album from 2009, This is the Life. On it are their most popular songs to date: “Cool Down,” “Ehu Girl,” and “Dream Girl.” “Ehu Girl” is probably my ultimate favorite of his because it sort of (barely) matches my initials. My research found that an “ehu” girl is actually a term for a Polynesian girlie pop with uniquely blonde or reddish hair (definitely not me). From these titles alone, you’ve probably collected the distinctly beachy and nostalgic 2000’s surf crush-y vibe. Also vetted for KKS is their 2011 album, Love Town, with similar tracks. There’s a sweetness and a purity to Kolohe’s earliest songs, perhaps aimed at a pre-teen contingent (somehow, also, 25 year-old me). I mean, the group just wants to meet cute girls in line at 777 Karaoke and cool down by surfing monster waves.

As summer has rolled on, Kolohe Kai Summer has expanded to any and all local Hawaiian music – other favorites have become J Boog, Fia, Iam Tongi (“Why Kiki?” …get it? Waikiki?? Like the beach? ok sorry), Israel Kamakawiwo’ole (the absolute *chokehold* his “Over the Rainbow” recording had over little middle school me – and somehow we’re already back to Judy Garland?), The Green, Maoli (the king of island-inspired re-recordings of country favorites), Jack Johnson (who half-qualifies – born and raised in HI but not native… nature vs. nurture? Still love him, whatever), Anuhea (baddie), and Three Plus (hoooooney babaaayyyy). All saved here: cherry-picked: Kolohe Kai Summer.

When we make our way to Honolulu to race and relax in December, I will absolutely be dragging us to not only the temporarily closed “Club Triple 7” of “Ehu Girl” glory but also the Hawaiian Music Hall of Fame in downtown Honolulu. In a state–sorry, nation–so rich in cultural history, natural beauty, and musical supremacy, eight days will simply not be enough time to learn and appreciate all that Hawaii and Hawaiian music is. While tourism is a boon to Hawaii’s local economy, I’m deeply aware of how extractive tourism can be. It’s not much, but in order to be more additive than extractive, I’ve massively upped my listenership of these independent Hawaiian artists, and I’m fundraising for Shriners Children’s Hospital Honolulu, which provides specialty care to local kiddos (if you feel so led to contribute here!!).

I can’t wait to see and feel more of the scenes that have inspired the sounds of my summer 2025. Kolohe Kai Summer lives on, and a hui hou (see ya soon), Honolulu!

Leave a comment